Innocent infringement – is ignorance really bliss?

Anyone seeking to commercialise a product in Australia faces the seemingly impossible task of determining whether they are likely to infringe anyone else’s patent rights. However, while a plea of ignorance might seem like a reasonable defence to patent infringement, it is a longstanding principle of patent law that the public is assumed to be aware of published patents and patent applications. The question arises – can ignorance of a patent ever be a valid defence to infringement? To answer this question, Beata Khaidurova examines the law of innocent infringement in Australia, and considers whether copyright law serves as a guide.

The infringer’s knowledge of a patent

With over 250,000 patents and patent applications currently active in Australia, and more being filed every day, it might seem that a plea of ignorance – “but I didn’t know about that patent!” – would be a reasonable defence to an accusation of patent infringement.

However, it is a longstanding principle of patent law that a patent application, once published, is presumed to be “known” (or at least discoverable) to the public. This principle makes sense as it prevents potentially infringing parties from intentionally turning a blind eye and refusing to search for patent documents that may be relevant to their activities. So when, if ever, can a party successfully assert they are innocent of infringement as they did not know that a particular patent existed?

The law of innocent infringement

While not strictly a “defence” to infringement, s123 of the Patents Act 1990 (Patents Act) does provide that a court may refuse to award damages to a patent owner where the patent infringer satisfies the court that, at the date of the infringement, “the defendant was not aware, and had no reason to believe, that a patent for the invention existed”. In this case, the infringing party may be known as an “innocent infringer”. However, as made clear from the language used, this section requires more than a mere ignorance of the patent in question. Instead, the infringing party must prove that they had no reason to even believe that a patent existed for the invention in question.

The question of what amounts to having “no reason to believe” that a patent existed for an invention was discussed in Axent Holdings Pty Ltd t/a Axent Global v Compusign Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1373 (Axent Holdings case), where the court provided some guidance as to the type of evidence that was required to satisfy the requirements of s123.

Axent Holdings case facts

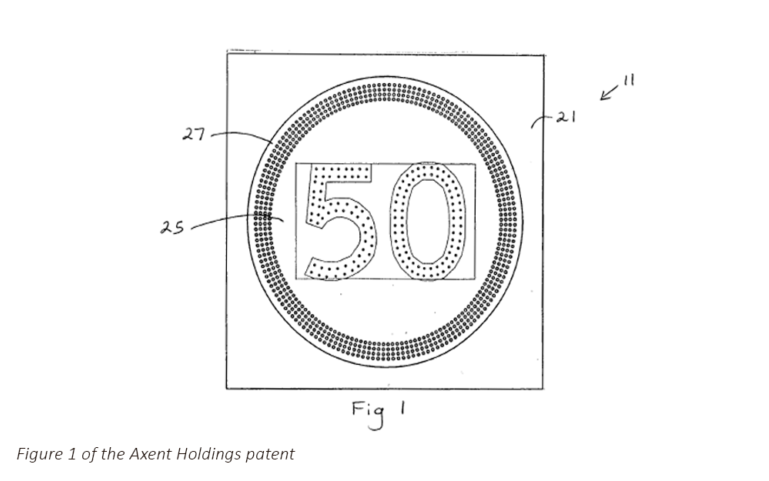

The Axent Holdings Australian patent 2003252764 was essentially directed to a changing sign system that was designed to be used as a variable speed limit sign for display on roadways.

Compusign Australia Pty Ltd (Compusign) manufactured and installed displays for the traffic signal industry throughout Australia. Axent Holdings alleged that Compusign had infringed all of the claims of the Axent Holdings patent by manufacturing variable speed signs that included each of the features claimed in its patent.

As well as alleging that the Axent Holdings patent was invalid, Compusign countered by filing a number of defences. Among these, Compusign asserted that they were not aware of the Axent Holdings patent until 16 September 2016. Consequently, any damages for infringement before this date ought to be refused under s123 of the Patents Act.

While the court ultimately found that the Axent Holdings patent was invalid, the court also considered whether, if there had been infringement, Compusign would have been found to be an innocent infringer under s123.

Compusign’s evidence

Despite the Axent Holdings patent being published on 22 April 2004, Compusign alleged that they were only made aware of the Axent Holdings patent on 16 September 2016, being the date they had received a letter of demand from Axent Holdings.

Compusign provided a number of facts to support their position. Among these was the fact that Compusign had designed their variable sign system to meet the requirements outlined in a tender document issued by VicRoads. These requirements outlined in the document were based on discussions VicRoads had had with Axent Holdings, and they included a number of features claimed in the Axent Holdings patent, such as the requirement that the sign include an inner red annulus that was capable of flashing on and off. However, nothing in the tender document provided to Compusign noted the existence of a relevant patent covering the required features.

Was there innocent infringement?

It was held that even if Compusign had been found to infringe the Axent Holdings patent, innocent infringement would have been made out, and the court would have exercised its discretion to refuse damages for acts prior to Compusign being made aware of the patent on 16 September 2016.

Among other reasoning, the court considered that in the absence of contrary information, the documents provided to Compusign by VicRoads would have indicated to Compusign that the supply of a sign that met the requirements of the tender would not be constrained by any Australian patents. The court compared the case to a number of previous UK and Australian decisions in which innocent infringement failed, but found that the Axent Holdings case was distinguishable on the facts.

What appeared to persuade the court was reliance on a copyright law principle, which requires the infringer to have an active subjective lack of awareness, and no reasonable ground for suspecting that their act constituted an infringement of copyright. In particular, at paragraph [501] of the Axent Holdings case, the court makes reference to the Copyright Act 1968 (Copyright Act), noting that s115(3) of the Copyright Act is analogous to s123(1) of the Patents Act. The court used this analogy to strengthen its position in finding that innocent infringement would have been made out

How relevant is copyright law to patents?

Both the Copyright Act and the Patents Act regulate their respective intellectual property rights. But there are two fundamental differences between the laws set out in each Act.

Firstly, there is a well maintained electronic record of patents and patent applications. No such register exists for copyright material. Therefore, to determine the existence of relevant patents/applications simply requires a search of these electronic records. Secondly, a finding of copyright infringement requires proof of copying of a work. There is no equivalent requirement in patent law.

Based on these two significant differences, it is evident that copyright law is irrelevant to an innocent infringement assessment under the Patents Act. Whilst it may be that conduct of the tender process in this case was sufficient to justify a finding of innocent infringement, the reliance on a seemingly analogous provision in the Copyright Act is inappropriate.

Best practice to minimise infringement risk

While innocent infringement may still be a defence in some limited circumstances, best practice continues to be that of performing relevant searches before undertaking significant commercialisation steps.

An often used initial search strategy is to conduct a landscape search to provide an overview on patents/applications of relevance. Once the technology has been progressed in development, a more targeted “freedom to operate search” should be undertaken. In this way, potential infringements may be avoided or at least the risk of infringement reduced.