CAR-T cell therapy: Understanding the patent landscape

The CAR-T cell patent landscape has seen exponential growth in the past decade. This article, the third in a series, highlights the significance of understanding third-party patent rights for effective decision-making in the development and commercialisation of CAR-T cell technology. Discover essential insights on patent landscape analysis for CAR-T development.

The CAR-T cell patent landscape has grown exponentially over the last 10 years, with Big Pharma players including Novartis, Gilead Sciences’, Kite Pharma and Bristol Myers Squibb’s Juno Therapeutics1. Part 1 and Part 2 of this series discuss strategic considerations regarding protecting CAR-T cell assets. This article turns to the importance of understanding and evaluating the patent landscape with respect to third party patent rights.

As discussed in Parts 1 and 2 of this series, patents to CAR-T cells not only encompass the CAR-T cell per se, but also encompass the individual components of the CAR-T cell construct, manufacturing processes and methods of use. Neglecting to develop an appropriate understanding of the patent landscape can be costly, as demonstrated by the staggering USD$778 million damages that was initially awarded to Juno Therapeutics against Kite Pharma2 (a decision that was later reversed) for infringement of claims related to CAR-encoding nucleic acid polymers.

Part 3: Insights into patent landscape analysis and freedom-to-operate

A freedom-to-operate (FTO) analysis is a detailed analysis of the patent landscape which aims to assess whether or not a third-party’s right(s) may be infringed by a proposed commercial product or process. Typically, a FTO analysis involves a full review of a commercial product or process, or at least the significant components in isolation and together, and needs to be conducted in every country where the product (or process) will be commercialised. More often than not though, during early research and development, what is required is a patent landscape analysis. In contrast to a FTO, a patent landscape analysis typically involves a focused review of the patent landscape with a view to identifying key (rather than all) relevant patents covering a product.

Depending on the extent of analysis required, searching typically entails:

- a review of third-party patent rights

- a review of known competitors by owner or inventor searches

- identification of potential roadblocks (i.e. granted patent claims)

- analysis of the scope, validity and enforceability of any potential blocking patents

- monitoring of published relevant applications and regularly updating the searching/analysis.

Targeted searches for CAR-T Cell innovators

CAR-T cell companies focused on research and development, and ultimately commercialisation, of the next generation of CAR-T cell therapies should give consideration to each component of the CAR-T cell product, the intended therapeutic uses and, any other aspect associated with preparation or delivery of the CAR-T cell product.

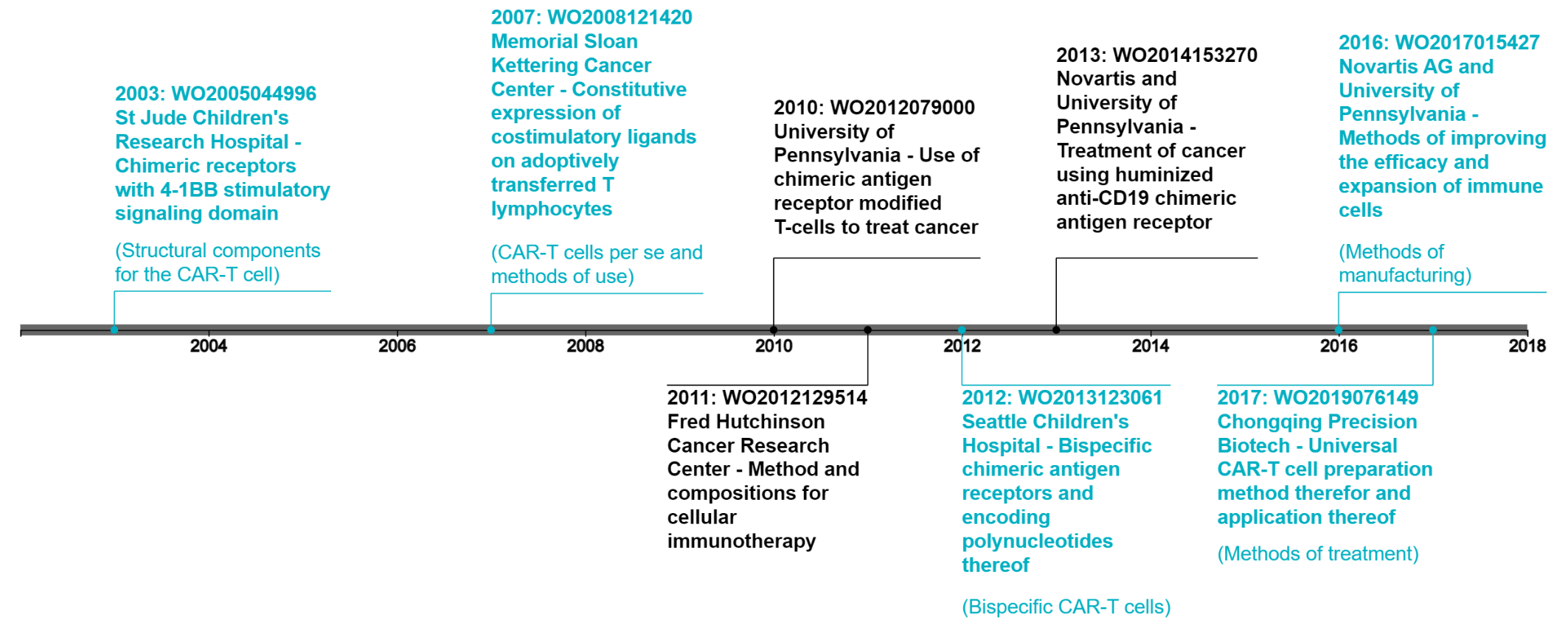

A number of key foundational patents associated with CAR-T cell technology were filed in the early 2000’s3 and are expected to expire within the next 5 to 10 years. However, as shown in the figure below, patent applications continue to be filed covering many different aspects of the CAR-T cell which should be considered during any landscape analysis.

In addition to the above elements, other exemplary searches may include:

- components of the CAR including the binding domain, transmembrane domain, signaling domain, and co-stimulatory domains

- additional structural components of the CAR, such as safety switches and immune-checkpoint modulators

- altered functionality (e.g., altered T cells for universal cytokine-mediated killing (TRUCKs)

- intended therapeutic use (e.g. methods of treatment)

- co-therapies (e.g., if patients are receiving pre-conditioning treatments)

- methods for delivery of the CAR-encoding polynucleotide (e.g., CRISPR and zinc-finger nucleases)

- methods related to engineering the CAR-T cells

- methods related to culturing and expanding the CAR-T cells

- changes to the manufacturing method (particularly those that enhance productivity or yield)

- compositions and methods for characterising CAR-T cell populations (e.g. potency assays)

- devices / culture systems per se.

Whilst a combination of components may give a CAR-T cell product enhanced activity or potency, third party owned patents may act as a barrier to commercialisation even if they only cover part of the combination. Accordingly, it is important to consider searching each element of a CAR-T cell separately.

Guide to strategic patent landscape analysis

Whether you are a startup, a research institution, contract manufacturer, investor or Big Pharma, patent landscape and freedom-to-operate (FTO) analysis allows informed decisions to be made before investing considerable resources, such as time and capital, into product development and manufacturing. The type and extent of searching required is often dictated by a company’s budget, commercial activities, and objectives. Below we discuss some of the main considerations start-ups, manufactures and Big Pharma may wish to consider when undertaking patent landscape analysis.

Start-ups/R&D

In view of the early stage of their technology and cost considerations, start-up and early-stage companies may consider targeted searching to understand whether key patents have been filed which cover their product. Companies can then develop a strategy for navigating any key patents that is sufficient to satisfy potential investors or commercial partners. This type of patent landscape analysis can also be useful for:

- identifying potential collaborators or partners

- identifying potential licensing opportunities

- identify areas of patentability associated with their CAR-T cell product or process.

Manufacturers

Similar to start-ups, it is important for CAR-T cell manufactures to be aware of the patent landscape surrounding their manufacturing process. Currently, with autologous CAR-T cell products manufacturing methods are tailored to production of the specific CAR-T cell rather than use of a ‘platform’ process. This lends itself to manufactures preferring to protect proprietary methods as confidential information, rather than by obtaining patent protection. However, with a global drive towards scalable manufacturing methods that can reduce “vein-to-vein” time, as well as production of “off the shelf” CAR-T cell products, it is important for manufacturers in this space to understand the patent landscape to identify any potential barriers to market entry and/or third-party patents that cover their current commercial activities.

Big Pharma

Commercialisation entities such as Big Pharma generally undertake more extensive searching or FTO analysis as they need to have a more detailed understanding of all patent barriers to market entry and how these will be circumvented. This will typically involve a full review of third party patent rights in view of the commercial product or process, analysis of the scope, validity and enforceability of any identified blocking patents and monitoring of any identified relevant applications through regularly update searches. Due to the jurisdictional nature of patent rights, such searching and analysis needs to be conducted in every country where the product (or method) will be manufactured and/or commercialised.

Strategising CAR-T Cell patents

CAR-T cell therapy is a rapidly growing, innovative approach to cancer therapeutics. Many patent applications have been filed and granted covering various aspects of CAR-T cell technology. Understanding the complex patent landscape through well-designed searches is an integral part of any CAR-T cell patent strategy. Early identification of blocking patents provides opportunities for mitigating risks, including design around, licensing opportunities or developing/mounting attacks against problematic patents.

Collaborate with our IP strategy team

Are you working in the CAR-T cell or broader personalised cell therapy space? Our IP strategy team is here to collaborate with you. Contact us today to steer your CAR-T breakthrough with an effective patent approach.

Footnotes

See Lyu et al., 2020 Nature Biotechnology, vol 38, pp. 1387-1395 for a review of the milestone CAR-T patentees and patents.

Juno Therapeutics, Inc. et al. v. Kite Pharma, Inc., No. 2-17-cv-07639 (C.D. Cal.)

See Lyu et al., 2020 Nature Biotechnology, vol 38, pp. 1387-1395